- Cmake Basic Example Free

- Cmake Basic Example Pdf

- Cmake Basic Example Of Business

- Cmake Basic Example Of Research

Canon 5d mark iii shutter count check. The end of a semester is here and, as I grade our student's semestral works, I get to use Makefiles and CMakeLists of dubious quality[1]. After seeing the same errors repeated over and over again, I decided to write a short tutorial towards writing simple Makefiles and CMakeLists. This is the CMake tutorial, the Make one can be found here.

Basic CMake usage By Martin Hořeňovský May 20th 2018 Tags: CMake, Tutorial, C. The end of a semester is here and, as I grade our student's semestral works, I get to use Makefiles and CMakeLists of dubious quality. After seeing the same errors repeated over and over again, I decided to write a short tutorial towards writing simple Makefiles.

- There are some useful tutorials linked on the CMake Wiki but most of them only cover very specific problems or are too basic. So I wrote this short CMake introduction as a distilled version of what I found out after working through the docs and following stackoverflow questions.

- A compiler/build system (visual studio, OSX, g, etc.) Start a command prompt!! Do a recursive checkout of this example: git clone -recursive Move into the directory. Cd simplecmakeexample. Make directories. Mkdir build && cd build.

Through these tutorials, I'll use a very simple example from one of our labs. It is start of an implementation of growing array (ala std::vector), consisting of 5 files:

Vs2015. Download previous versions of Visual Studio Community, Professional, and Enterprise softwares. Sign into your Visual Studio (MSDN) subscription here. System requirements for the Visual Studio 2015 family of products are listed in the table below. For more information on compatibility, please see Visual Studio 2015 Platform Targeting and Compatibility.For Visual Studio 2017, see Visual Studio 2017 Product Family System Requirements. To view system requirements for specific products, click on a bookmark below. Download Visual Studio 2015. To download Visual Studio 2015 Update 3, click on the download button. The files are downloaded from our free Dev Essentials subscription-based site.

main.cppvector.hppvector.cpparray.hpparray.cpp

Their exact contents do not matter[2], but main.cpp includes vector.hpp, vector.cpp includes array.hpp and both vector.cpp and array.cpp include their respective headers, vector.hpp and array.hpp.

It is important to note that these tutorials are not meant to build a bottom-up understanding of either of the two, but rather provide a person with an easy-to-modify template that they can use for themselves and quickly get back to the interesting part -- their code.

CMake

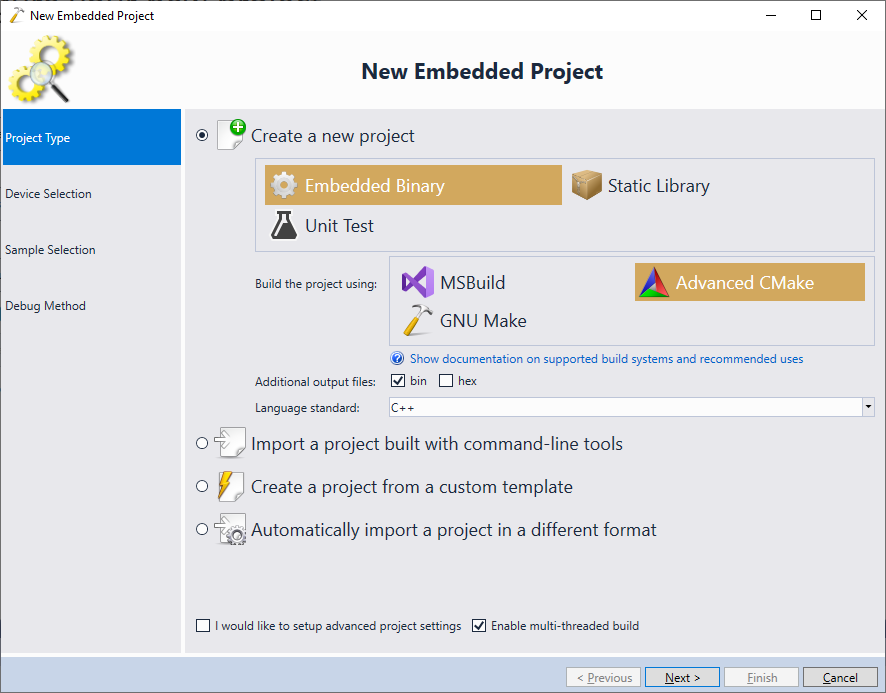

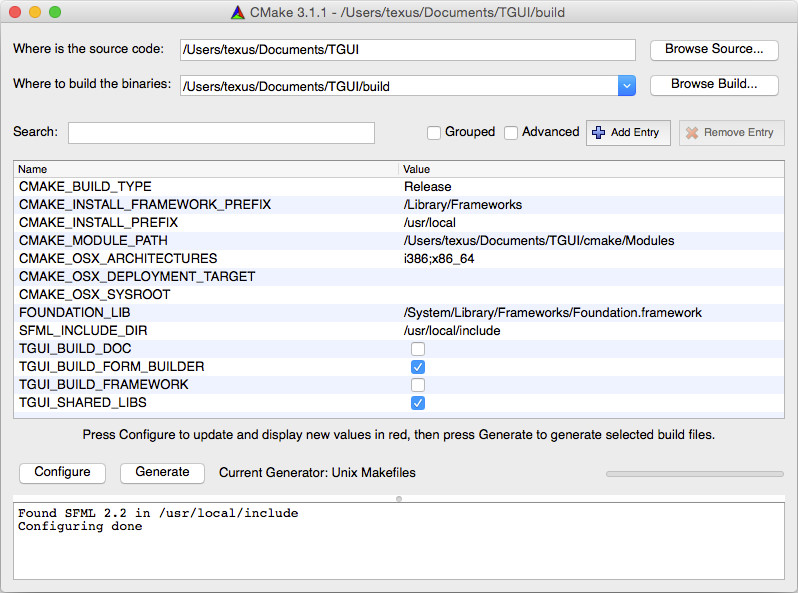

CMake is cross-platform meta build-system. What this means is that CMake does not build things, it generates files for other build systems to use. This has a number of advantages, e.g. it can output MSBuild files for Visual Studio when used on Windows, but can also output makefiles when used on Linux.

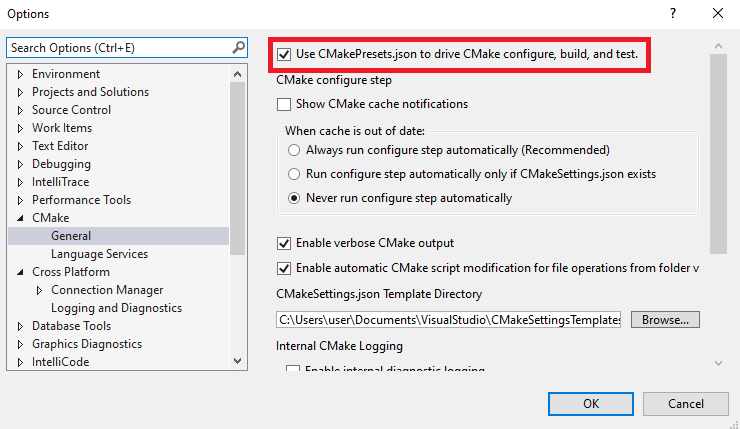

CMake works by reading a single input file named CMakeLists.txt and generating platform-specific files for different build systems from the declarations and commands within. A large problem with CMake is that there are many tutorials giving bad advice, including its own documentation[3].

This is an example of CMakeLists.txt that contains two fundamental problems, that are painfully common.

The first problem is that it is non-portable because it sets GCC/Clang specific flags (-Wall, -std=c++14) globally, no matter the platform/compiler. The second is that it changes compilation flags and include paths globally, for all binaries/libraries. This is not a problem for a trivial build like this, but as with many things, it is better to get into the habit of doing things the correct way right from the start.

The proper way, sometimes also called modern CMake, minimizes the use of global settings and combines using target-specific properties with CMake's understanding of building C++. The modern CMake version of the CMakeLists.txt for the same toy problem is this:

Notice that we had to bump the required CMake version for this to work. We also told CMake that this project will use only C++ -- this cuts down the time it needs to create projects, as it does not have to look for a C compiler, check if it works, etc.

The desired C++ standard is still set globally. There are some arguments for setting it per-target, and some good arguments against[4], but at the time of writing this I am against setting C++ standard per-target.

Setting CMAKE_CXX_STANDARD to 14 tells CMake that we want to add whatever flags are needed for our compiler to be able to compile C++14. For GCC/Clang this is -std=c++14 (or -std=gnu++14), for MSVC this is nothing (it supports C++14 by default). Enabling CMAKE_CXX_STANDARD_REQUIRED tells CMake to fail generation step if C++14 is not supported (the default is to keep going with older standard) and disabling CMAKE_CXX_EXTENSIONS tells CMake to prefer flags that do not enable compiler-specific extensions -- this means that GCC will be given -std=c++14 rather than -std=gnu++14.

You might have noticed that there are now no warnings. This is a bit of a sore spot because CMake does nothing to help you with setting (un)reasonable warning levels in a cross-platform fashion, so you have to do it yourself, by using appropriate flags for each compiler, like so[5]:

With this, we have a CMake build file that lets us build our toy project with GCC/Clang on Linux/OS X/BSD/others and with MSVC on Windows, with a reasonable set of warnings and using C++14 features. Note that we did not have to do any work to track dependencies between files, as CMake does that for us.

Generated project

The provided CMakeLists.txt template works well for building the project, but does not generate good project files, as it just dumps all .cpp files into a project, without any grouping or headers, as shown in this picture:

We can fix this by changing the CMakeLists.txt a bit, and add the header files as components of the executable. Because CMake understands C++, it will not attempt to build these header files, but will include them in the generated solution, as shown in this picture:

Let's pretend for a bit that our project has grown, and we would like to have extra folders for grouping our files, e.g. 'Tests' for grouping files that are related to testing our binary, rather than towards implementing it. This can be done via the source_group command. If we decide to use main.cpp as our test file, we will add this to our CMakeLists.txt

The result will look like this:

Tests

Cmake Basic Example Free

The CMake set of tools also contains a test runner called CTest. To use it, you have to request it explicitly, and register tests using add_test(NAME test-name COMMAND how-to-run-it). The default success criteria for a test is that it returns with a 0, and fails if it returns with anything else. This can be customized via set_tests_properties and setting the corresponding property.

For our project we will just run the resulting binary without extra checking:

That weird thing after COMMAND is called a generator-expression and is used to get a cross-platform path to the resulting binary[6].

Cmake Basic Example Pdf

Final CMakeLists.txt template

After we implement all of the improvements above, we end up with this CMakeLists.txt:

Setting CMAKE_CXX_STANDARD to 14 tells CMake that we want to add whatever flags are needed for our compiler to be able to compile C++14. For GCC/Clang this is -std=c++14 (or -std=gnu++14), for MSVC this is nothing (it supports C++14 by default). Enabling CMAKE_CXX_STANDARD_REQUIRED tells CMake to fail generation step if C++14 is not supported (the default is to keep going with older standard) and disabling CMAKE_CXX_EXTENSIONS tells CMake to prefer flags that do not enable compiler-specific extensions -- this means that GCC will be given -std=c++14 rather than -std=gnu++14.

You might have noticed that there are now no warnings. This is a bit of a sore spot because CMake does nothing to help you with setting (un)reasonable warning levels in a cross-platform fashion, so you have to do it yourself, by using appropriate flags for each compiler, like so[5]:

With this, we have a CMake build file that lets us build our toy project with GCC/Clang on Linux/OS X/BSD/others and with MSVC on Windows, with a reasonable set of warnings and using C++14 features. Note that we did not have to do any work to track dependencies between files, as CMake does that for us.

Generated project

The provided CMakeLists.txt template works well for building the project, but does not generate good project files, as it just dumps all .cpp files into a project, without any grouping or headers, as shown in this picture:

We can fix this by changing the CMakeLists.txt a bit, and add the header files as components of the executable. Because CMake understands C++, it will not attempt to build these header files, but will include them in the generated solution, as shown in this picture:

Let's pretend for a bit that our project has grown, and we would like to have extra folders for grouping our files, e.g. 'Tests' for grouping files that are related to testing our binary, rather than towards implementing it. This can be done via the source_group command. If we decide to use main.cpp as our test file, we will add this to our CMakeLists.txt

The result will look like this:

Tests

Cmake Basic Example Free

The CMake set of tools also contains a test runner called CTest. To use it, you have to request it explicitly, and register tests using add_test(NAME test-name COMMAND how-to-run-it). The default success criteria for a test is that it returns with a 0, and fails if it returns with anything else. This can be customized via set_tests_properties and setting the corresponding property.

For our project we will just run the resulting binary without extra checking:

That weird thing after COMMAND is called a generator-expression and is used to get a cross-platform path to the resulting binary[6].

Cmake Basic Example Pdf

Final CMakeLists.txt template

After we implement all of the improvements above, we end up with this CMakeLists.txt:

It provides cross-platform compilation with warnings, can be easily reused for different sets of source files, and the generated IDE project files will be reasonably grouped.

Closing words

Cmake Basic Example Of Business

I think that both Make and CMake are terrible. Make is horrible because it does not handle spaces in paths, contains some very strong assumptions about running on Linux (and maybe other POSIX systems) and there are many incompatible dialects (GNU Make, BSD Make, NMake, the other NMake, etc.). The syntax isn't anything to write home about either.

Cmake Basic Example Of Research

CMake then has absolutely horrendous syntax, contains a large amount of backward compatibility cruft and lot of design decisions in it are absolutely mindboggling -- across my contributions to OSS projects I've encountered enough crazy things that they need to be in their own post.

Still, I am strongly in favour of using CMake over Make, if just for supporting various IDEs well and being able to deal with Windows properly.

Last time we didn't teach either, but we will probably add a short introduction to both to the next semester. ↩︎

In case you do care, here is a link to one of the zips that contains them. ↩︎

The problem with CMake documentation is that it is fully descriptive. This means that it tells you everything that can be done but omits what should be done and why. This makes them mostly useless, and most of useful CMake knowledge propagation is done using word-of-mouth and tribal knowledge. ↩︎

The arguments against setting C++ standard per-target are centered about ABI breakage, e.g.

std::string's representation when compiled with-std=c++98could be radically different from its representation when compiled with-std=c++11. In practice, the offending stdlib (libstdc++) has a separate define that guards the ABI break, and implementations of the standard library go into significant pain to ensure that these sort of errors fail at link-time. However, almost any type can have different representation across different standards (and even across different#defineset), and very few libraries take the necessary steps to ensure detection during linking, leading to binaries that fail at runtime in completely non-sensical ways. The arguments for setting the standard per-target is that this does not have to happen and you can, e.g. keep a library compiled with an old standard, while your binary can use newer one. ↩︎These were taken from Catch2's CMakeLists.txt at the time of writing. ↩︎

Generator expressions also happen to be one of the crazier parts of CMake syntax. ↩︎